Chapter 9

Effects of the Sun, Maladies, etc.

The #1 Threat

My Travel Clinic

Self-Diagnosis

Playing Doctor

Maladies

Items of the Colon

Food Poisoning

Rehydration Therapy

Women's Concerns

AIDS

Insects...Urine Fish

Mosquitoes

Wounds, Rashes

Foot Care

Effects of the Sun

Cold and Frostbite

Altitude Sickness

Jet Lag

Medical Kits

Returning

Home Tips

IN NORTH AMERICA, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Japan, and a few other

places your most likely health problems are foot blisters, colds, constipation, and

hangover. In the rest of the world most travelers are likely to encounter nothing more

than mild diarrhea from unfamiliar microbes introduced into the intestines.

Don't allow fear of health problems forestall developing world travel--if you sit at

home you might have a heart attack or develop a horrible disease of the ass! While

headline-grabbing diseases such as Ebola, Lassa Fever, and plague are terrifying,

travelers don't get them. These are diseases of grinding poverty and

ignorance. For twenty years we of the developed world have been suffering the

deadliest and most insidious virus of all--so try to maintain perspective.

With the sensible precaution of seeking and following advice from a travel clinic your

health risks are greatly reduced, as most risks are directly related to awareness. You

don't want to be as naïve as I on my first backpacking trip into the developing world.

(See photo below and Drinking Tips in Chapter

21.)

|

Photo: Here I'm feeling chipper

compared to a few hours earlier. Note the language dictionary in my right hand--the doctor

spoke English, the nurses did not. Many thanks for the wonderful care from

all. |

By far the greatest threat to the traveler is being run over by a moving vehicle, or

from a crash while in a moving vehicle. Even for Americans on comparatively safe American

roads there is about a one in one-hundred lifetime chance of perishing in an automobile

accident, and many times that for serious injury.1

Therefore the most important steps for traveler safety are obvious--always wearing a

seat belt or helmet, always looking both ways before crossing a street, and standing well-back from

the curb. Keep this in mind as you read about malaria, cholera, and urine fish.

Driving in Developing Countries and Remote Areas

(Chapter 21 Considerations)

From a March 1997 email (bottom)

Sources For Current Information

If planning a journey to the developing world, this chapter will not provide

all the information you need. That information is not available in any book, as epidemics

and outbreaks occur and change much too quickly. Constantly updated information is

available from:

Centers For Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia (voice tel. 404-332-4559 fax-back

888-232-3299)

cdc.gov

The CDC webpage is used by travelers from everywhere for the latest worldwide disease

and health information. You can also listen to exhaustive recordings of health information

over the phone by requesting specific topics via touch tones, or use their fax-back

service. Many travel clinics receive software updates from the CDC, and provide that

information to customers, one of which you should be before and after developing world

travel.

Most major cities have a private or public travel clinic to assist international

travelers with preventive measures, and to treat diseases brought back. After being

pitifully laid out and hospitalized on my first tour into rural Mexico due to stupidity,

there was no question that before my next journey into the developing world I would seek a

travel clinic and spend whatever necessary to get fully immunized, as well as medically

and mentally equipped.

Soon I had the opportunity for a few months in Central America, so I made an

appointment with the Travel Clinic in Austin, Texas. During the initial $45 visit a

knowledgeable Registered Nurse discussed my case. She also had access to a computer file

from a private company called Travax, which was a compilation of information from the CDC

and the State Department. It was updated weekly.

I was given forty pages of useful computer printout on eight Central American

countries. Topics for each country were AIDS, cholera, malaria, hepatitis, polio, rabies,

typhoid, yellow fever, cholera, insect-borne diseases, food and water-borne diseases,

testing requirements, and a general description of each country. Most eye-opening were

U.S. Department of State travel advisory reports, including descriptions of recent

criminal activity against travelers, warnings about possible drug penalties, assessments

of medical facilities, and embassy locations and phone numbers.

On my first visit to the clinic I received a polio booster shot in one arm ($25) and a

tetanus-diphtheria (Td) booster shot in the other ($15). Both arms were slightly sore at

the place of injection for two days.

I was given prescriptions for chloroquine, Cipro, and a Typhoid oral vaccination.

Chloroquine is an anti-parasitic drug which usually kills malaria-causing protozoa in the

blood. It is taken once weekly beginning one or two weeks before entering an infected

area, and for four weeks after leaving an infected area. I bought the generic chloroquine

for about $2.50 per capsule--$1 less than the brand name.

Cipro is a brand of ciprofloxacin antibiotic available through prescription. It is

effective against travelers' diarrhea since it causes fewer side effects than

broader-ranging antibiotics. Recommended dosage was one 500 mg tablet twice per day for

three days. Cost was $20 for six tablets, but I bought twelve as Cipro has a long

shelf-life, and I knew from experience how vital an effective antibiotic could be.

I was instructed to carry Cipro, Immodium, and a thermometer. If I contracted mild

diarrhea, which was defined as several bowel movements per day while feeling fairly well, no

treatment was indicated. If the diarrhea was severe I was instructed to check my

temperature. If it was above normal I was to take 500mg of Cipro twice per day for three

days. If my temperature was normal, I was to take the Cipro as above, and to take

one Immodium tablet four times per day for three days.

The reason for not taking the Immodium while running a fever is that fever may indicate

organisms in the bowels which are likely to invade the intestinal lining. Since Immodium

slows intestinal movement (plugs you up), it would allow the bad bacteria a better chance

to invade the lining and prolong diarrhea.

I was also told to seek medical help if self-treatment did not work, and if there was

accompanying high fever, blood, or mucus in the stool, which are all indicators of

infection.

The Oral Typhoid Vaccine cost $42 and consisted of four capsules to be taken with cool

water one hour before meals every other day. Since this was a live vaccine the capsules

had to be kept cool. I was given an ice-pack for transport home. This oral vaccine was

said to have fewer side effects than the injectable version.

About ten days later I returned to the Travel Clinic for an immunoglobulin

(gammaglobulin) injection ($9) in the hip, and a yellow fever vaccination ($52) in one

arm. The immunoglobulin shot contained antibodies to combat Hepatitis A, which provides

some protection for up to five months. It should, however, be taken as close to departure

as possible to ensure maximum effectiveness. The yellow fever shot is effective for ten

years.

After this second visit to the Travel Clinic I had a very slight fever and chills, and

was slightly tired for a few days. This was considered a normal reaction. My hip

definitely ached from the immunoglobulin shot.

Find a travel clinic in your area by checking the yellow and white pages under Travel

Clinics, or by calling your local public health agency, hospital, or doctor.

International Health Certificate (Yellow Card)

This card documents your immunization history. Required for entry to some countries for

proof of yellow fever inoculation, it is available from travel clinics, and possibly your

doctor. It's yellow.

Travel Health Insurance

Many companies sell travelers' health insurance for one to several dollars per day.

Usually you pay the medical costs while abroad, but are reimbursed upon return. More

expensive plans pay for emergency air transport home.

If you already have health insurance check if your current plan provides coverage in

other countries. There's a good chance it does, though it probably won't cover emergency

air transport.

ISIC (International Student Identity Card) holders get coverage with the card. Other

plans are available from many travel agents, including Council Travel and other

budget/student specialists. Search the web or see Chapter

23-b Useful Information for a dozen companies that offer travel insurance.

Some European and other advanced countries with national health systems treat--at no

charge--travelers from other countries on a reciprocal basis. Citizens of the United

States, of course, are on their own.

The knowledge base doctors use to diagnose is a thousand times greater than the

following list of symptoms and disease characteristics. Don't try to diagnose yourself or

someone else--seek professional advice as soon as you can. Even in developing countries

where doctor training may not be extensive (in Mexico I was superbly treated by a

twenty-two-year-old), they will be familiar with local health problems.

Another point is that treating yourself with too few or the wrong antibiotics can be

seriously unhealthy. The wrong antibiotics can facilitate germ entry into new areas of the

body, while too few might allow the infection to spring back worse than before.

Learn from my mistakes!

- You may not notice a slightly elevated rate of breathing, or if you do, you may not

connect it with rapidly developing pneumonia. You may also be fooled (not that you have

any knowledge or experience to fool) because the patient's symptoms (temperature,

vomiting, etc.) appear (to you) to be improving. The situation can suddenly change for

much worse or disaster due to something under the surface of what untrained and

inexperienced eyes can see.

- "What's going around" may have relevance in a macro sense, but it may also

have little or nothing to do with your patient/friend/loved one due to age, health,

medication, etc.

- Don't put too much stock into advice over the phone (unless it's to seek professional

help right away), even if it's from a good source. The difference between a description by

someone with nearly zero experience and the patient being seen by a medical professional

is like night and day.

- Many lives could be saved and much suffering avoided if people who basically don't know

anything (unless you're a doctor or nurse, that's you!) would get successively wiser, more

experienced, better educated, better trained hearts and minds involved to help think and

make decisions. This should be done in minutes or hours, not days.

- Get her the best trained, best equipped, and most compassionate care available. While

this must be balanced with time/distance/transport factors, it's probably wise to go

sooner for the superior care.

- If you are the patient, don't downplay your symptoms. The doctor needs to know exactly

how it is so he can make good decisions. In one case the patient kept telling the doctor,

"It's probably nothing, I'm okay," etc., when in fact he was having a major

heart attack with a lot of pain!

- It can be especially difficult if you normally rely on the patient/friend/loved one for

decision-making help, but the patient is too sick to provide reasonable guidance. Seek

professional medical help right away!

- You must act to preserve life, ease suffering, and increase joy by properly valuing your

patient/friend/loved one as early as possible, and by getting professional medical help as

soon as possible.

Maladies of Interest to Travelers

The following is a concise overview of major threats facing travelers. I hope it

encourages you to seek professional medical advice from a travel clinic before visiting

the developing world.

Most of this information came from the CDC, my travel clinic, the American Medical

Association Encyclopedia of Medicine, several travelers' health books, and my limited

experience. While I have tried to be accurate and informative, please

understand that I am

writing outside my fields of expertise (travel gear, hitchhiking, women), that I am neither a doctor or nurse, and that the best and only course of

action is to see a medical professional.

- Colds

- are common among travelers. One had five over six months in

Europe. He was also drinking more alcohol than usual, and not eating well. Because there

are over two hundred viruses associated with colds, those prevalent in Europe or China may

quickly overwhelm your immune system.

- Since colds are transmitted primarily by direct contact, incidence is reduced by washing

hands, especially before eating, and by keeping fingers away from the face. Colds

gain initial foothold in mucous membranes, so drink plenty of fluids to keep them in

good shape.

-

- Diphtheria

- is very rare in developed countries due to widespread use of the Td vaccine, but

is

still endemic in poor, developing countries, and a hazard to non-immunized travelers.

There is currently a diphtheria epidemic in the countries of the former Soviet Union.

-

- Diphtheria is an acute (suddenly developing) bacterial illness which causes a sore

throat and fever, and can be life-threatening when the bacteria release a toxin into the

bloodstream. About ten percent of victims die. Prevention is by updating your Td

vaccine.

- Tetanus

- is also called lockjaw. 500,000 cases develop annually worldwide, but only about one

hundred in the U.S. due to widespread immunization with the Td vaccine. While a booster is

recommended for the general population every ten years, the vaccine's effectiveness falls

off enough that if you get a major cut or puncture between years five and ten, it's

apparently standard practice to get another booster. (Hence I'll get a booster every five

years for developing world travel.)

- Symptoms include stiffness of the jaw, back, and stomach muscles, and a contraction of

facial muscles. Wounds should be thoroughly cleaned and an antiseptic applied. Tetanus is

serious and sometimes fatal. Prevention is by the Td vaccine.

- Diarrhea

- is often contracted by visitors to the developing world for a few days. It is generally no

great problem, and the discomfort usually lessens after a day or two.

- Diarrhea is most often caused by unfamiliar bacteria. Mexicans

traveling in the U.S. sometimes get Uncle Sam's Revenge. Anxiety is also a

precipitator.

- It's best to let normal diarrhea run its course, which takes two to five days.

Drink plenty of liquids to flush-out your system, and to avoid dehydration. Eat no solid

foods on the first day. On the second day begin eating bland foods such as toast, soup,

rice, and bananas.

- If you need to plug your system for a day so you can travel, the over-the-counter

drug Immodium works safely and well. The active ingredient in Immodium is loperamide,

which is also used in several other medications. Do not use loperamide for extended

periods as the intestines must be cleansed naturally. Loperamide doesn't cure anything.

- Many travelers swear by Pepto Bismol tablets for soothing the stomach and easing

diarrhea. I usually have these tablets in my pack, and when traveling developing

countries, several in my wallet. Pepto Bismol turns your stool a dark black.

- Dysentery

- is a severe infection of the intestines, characterized by passage of mucus and blood. It

has two forms: bacillary and amebic. While both are prevalent in many developing

countries, they are rare in travelers compared to simple diarrhea.

- Bacillary dysentery

- is also called shigellosis, after the shigella bacteria which cause it.

Bacillary means "rod shaped," which describes the bacterium. The usual source is

from infected food handlers failing to wash hands properly, and from flies landing

on food after having been somewhere nasty.

- Symptoms begin one to four days after infection, and are characterized by a sudden

onslaught of watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, vomiting, nausea, and fever. After several

days blood and mucus begin passing. It is highly contagious.

- Treatment consists of rehydration therapy. Solid food should not be eaten for the first

day or two. Antibiotics may be useful. Most victims begin recovering after about a week.

Babies, children, and old people risk death due to dehydration.

- Amebic dysentery

- is also called amebiasis, from the single-celled ameba (smallest animal)

parasite entameba histolytica. Amebic dysentery results from swallowing the

histolytica cysts via infected water or food (especially beware lettuce, uncooked vegetables, and

unpeeled fruit). It is found in the same areas as bacillary dysentery.

- Symptoms range from a few loose stools with rumbling pains in the stomach, to a severe

case with high fever and bloody, watery diarrhea. It comes-on slower than bacillary

dysentery. It can cause shaking chills, fever, weight loss, and painful enlargement of the

liver.

- Treatment is with rehydration therapy and amebicide drugs such as metronidazole, which

effect full recovery within a few weeks. It won't go away on its own like bacillary

dysentery.

Prevention for both types of dysentery is by eating only cooked vegetables and peeled

fruits, and by only drinking boiled or purified water.

I use the term food poisoning for three intestinal wars that for some reason went far

beyond the mild discomforts of travelers' diarrhea. Indeed I feel lucky to have survived.

The first is described in Drinking Tips in

Chapter 21. The second occurred on the last half of a three day bus journey after

mindlessly gobbling an apple purchased through a window and kindly presented by a fellow

passenger. While that was inconceivably stupid after months of incident-free travel in

very poor countries, I wasn't without luck. The bus was only half full and--miracle of

miracles--it had a working toilet.2

The third war played out in my apartment thanks to a now discontinued salad from an

American fast food restaurant.

While I can only describe the agony and weakness as nearly complete, here are a few

points should you find yourself in a similar situation.

1) Seek medical help if at all possible. Serious food poisoning

often kills, especially the young, the old, the weak, and those with pre-existing

conditions.

2) There may be a warning or premonition of your impending fate, so

take action while you can, such as:

- Notify someone, especially of authority

- Get to, or closer to, a doctor or clinic

- Make available lots of clean water or other nonalcoholic liquids

- Secure the best available environment

- Anything you'll be glad to have done in the few minutes you'll be lucky to have

3) After the initial wave of expurgations and you're well into

the dry heaves, drink clean fluids even when they soon come back up. This cleanses the

system faster, and the ten percent that is absorbed staves off dehydration. While clear

liquids are often recommended, I prefer any soft drink for extra energy and superior taste

in both directions.

4) Don't plug up your back end with drugs. The toxins must get

out. Pepto Bismol may help later.

5) Riding a speeding bus toilet for hours or days is supremely

unhealthy--better to get off when possible.

6) Flush, cover up, or crawl away from the horrific stench

immediately. Open vents to avoid explosion. (Or, 1. ...how the

driver was able to maintain consciousness. 2. If Sadaam should ever...)

7) Pray for God's help!

|

-

- Cholera

- results in severe water loss due to watery diarrhea and vomiting. The cholera bacterium

produces a toxin which increases the passage of fluid in the bloodstream to the

intestines. Death can result in a few hours from rapid fluid loss. Infection is by

ingesting food or water infected with the bacteria, but especially from shellfish. In two

hundred years cholera has spread from northeast India to most of the developing world,

including South and Central America, and Mexico.

- While the risk of cholera to travelers is slight, in 1993 in Guatemala City I read a full-page newspaper article about a

cholera outbreak/scandal in Chiquimula, a thriving middle-class city I had visited the

previous week. Water works employees had failed to chlorinate the water, and four hundred

people had come down with cholera, killing eleven.

- Symptoms begin one to five days after infection, and include diarrhea and usually

vomiting. Treatment consists of immediate rehydration therapy to prevent dehydration and

death. Ninety-nine percent of victims recover given adequate rehydration.

- Prevention consists of drinking only bottled or boiled water, and taking as much care

with food as possible. A vaccine is available, but is only about fifty percent effective

for three months. My travel clinic did not recommend the vaccine due to its

ineffectiveness, expense ($45), and the rarity of cholera in travelers. Other backpackers

have taken the vaccine because they were told it might reduce symptoms.

-

- Constipation

- is common due to the change in routine and diet. Make a point to drink plenty of fluids,

and eat roughage. Fighting has been reported in England over lettuce. Otherwise a pint or

two or three of Guinness provides relief.

Rehydration therapy is urgent in case of dehydration, usually due

to severe diarrhea and vomiting. It is especially crucial for infants and old people who

have suffered rapid water loss. Dehydration from diarrhea is the leading baby killer in

many developing countries. The two types of rehydration therapy are intravenous, performed

with a salt/sugar/water solution in the hospital, and oral, which can be done anywhere.

Oral rehydration solution consists of:

water: 1 quart or 1 liter

salt: 1/2 level teaspoon

sugar: 8 level teaspoons

sodium bicarbonate (baking soda): 1/4 teaspoon

The sugar aids absorption of the water and salt. Sodium

bicarbonate isn't necessary if unavailable. Be careful with measurements as too much salt

can increase dehydration. Dispose of unused solutions after twenty-four hours since

bacteria may multiply. Patients should drink more solution as able. A gallon or more may

be needed. Commercially prepared solutions to which you just add clean water are available

from pharmacies. It tastes vile, but you have to force yourself to drink it.

|

-

- Hepatitis type A

- is also called infectious hepatitis, and is the most common serious disease

among travelers in the developing world. Type A is transmitted by a virus through fecal

contamination, again via food or drinks prepared by an infected person with poorly washed

hands. While it is found worldwide, travelers are most susceptible in developing countries

with low food handling standards.

- Symptoms are either nonexistent or abruptly begin two to six weeks after exposure. They

resemble the flu, including fever, aches, loss of appetite, nausea, abdominal discomfort,

and liver pain (on your right side). Urine may darken, and stools may become lighter and

yellowish. After four to seven days the symptoms may become more severe, including

diarrhea, vomiting, itching, and jaundice. Skin and whites of the eyes may turn yellow.

Most recover within six weeks. Hepatitis type A does not lead to chronic hepatitis.

- There is no treatment for hepatitis A. Victims must rest and abstain from alcohol until

they recover. This recovery of the liver so weakens the victim they often can do no more

than hole-up in a fleabag hotel, or swing in a hammock under a palapa twenty hours per

day. Prevention is by taking care what and where you eat. An immunoglobulin shot provides

some protection for up to five months, the Havrix vaccine for up to ten years.

- Hepatitis type B

- is also called serum hepatitis. It is found in the blood, semen, and other body fluids

of infected persons. It is spread in the same manner as AIDS (sexual contact, IV drugs,

and infected blood products). Type B is found worldwide, but is much more prevalent in

Asia and Africa. Symptoms, when they occur, are the same as for hepatitis A, except

sometimes more severe. Many people are completely symptomless.

- About ten percent of hepatitis type B cases lead to chronic hepatitis, which is a severe

inflammation and destruction of cells within the liver. This leads to cirrhosis.

- Prevention is with the hepatitis B vaccine, although this is usually only recommended

for health care workers, people who have many unprotected-sex partners, and drug addicts.

Immunoglobulin

Immunoglobulin is also called gammaglobulin. It is a human plasma

product containing antibodies against measles and hepatitis A. Immunoglobulin is highly

recommended by the Centers for Disease Control for travelers staying at least three weeks

in areas of suspect hygiene and sanitation. It offers some protection for up to five

months. Since this protection fades with time, it is best to receive an IG shot just

before traveling to developing nations.

Immunoglobulin is composed of blood products, which in the U.S.

are screened for HIV and other diseases, rendering it safe, according to the CDC. Since

other countries may have shoddy or nonexistent screening, the CDC strongly advises not

getting immunoglobulin elsewhere. I would expect the odds of shoddy or nonexistent

screening for the U.K., Canada, Sweden, Germany, etc. would be the same or less than the

U.S., but that's a guess.

Havrix

A vaccine for hepatitis A called Havrix was introduced to the American market

in 1996. (Other brands were available in Europe for several years previously.) It requires

a booster after a year and is expensive at about $100, but offers more protection than

immunoglobulin and lasts up to ten years.

Consult with your doctor, of course, but the vaccine is probably worth the money as a

bad case of hepatitis A can seem Sisyphean at the very time you'd most prefer to be

healthy, and going back for IG shots is no fun.

|

-

- Typhoid

- is caused by the bacteria salmonella typhi. Feces, urine, and contaminated food and

water are the principal sources of infection--again often through a food handler with poor

hygiene. Sewage-contaminated shellfish is also a source.

-

- Most symptoms are limited to a fever of one week, but can include headache, anorexia,

general malaise, and constipation, giving way to diarrhea, a non-productive cough,

nosebleed, and raised pink spots on the upper abdomen. Complications may result, and the

death rate for serious cases is ten percent for those untreated, one percent for those

treated.

- Treatment is with antibiotics. Prevention is by cautious eating and drinking, and by an

oral or injectable vaccine, both of which are about sixty-five percent effective for five

years. The oral vaccine is four pills taken every other day; the injectable requires two

shots one month apart. The oral vaccine has lesser side effects.

- Antibiotics are not recommended as a preventive since they disrupt normal intestinal

bacteria and can facilitate infection with salmonella typhi.

- Polio

- is a viral disease which has been virtually eliminated in the developed world, but is

still a threat to non-vaccinated travelers in developing countries. Some beggars in

developing countries with wasted feet and legs are polio victims. There is no effective

treatment for polio. Prevention is with either the oral or injectable vaccine.

- Malaria

- poses the greatest health risk to travelers in warm climates, and is in fact

the greatest health threat to humanity. Up to 300 million cases occur worldwide each year,

with about one million deaths in both Africa and Asia. The tragedy is currently increasing

as mosquitoes become insecticide-resistant and forms of malaria become drug-resistant.

- Malaria is spread by the bite of the Anopheles mosquito, which generally feeds dusk

through dawn. It is caused by four types of a single-celled protozoa: vivax, ovale,

malariae, and falciparum. These parasites attack and explode red blood cells.

- Symptoms for the first three types may include the classic malarial fever, which is

called an ague (pron. ae gyoo). This occurs in three stages which rhythmically

coincide with millions of parasites being released into the bloodstream after bursting out

of red blood cells. First is a cold stage characterized by severe shivering, followed by a

high fever stage of up to 105º F (40º C). Finally there is intense sweating which brings

the fever down. The victim may also vomit and have a bad headache. The patient is left

weak and tired, and sleeps.

- These stages may occur cyclically, either every other day or every third day, but only

after the disease is well-established. Malaria can be very difficult to diagnose in

early stages.

- Falciparum is a more severe type of malaria as all red blood cells are

attacked. Death may result a few hours after symptoms begin. The brain may be affected,

and liver and kidney failure are common.

- Treatment is usually with a big dose of chloroquine. Falciparum malaria is resistant to

chloroquine, however, so other drugs must be used. Discuss treatment with your travel

clinic before you go, and immediately with local medical professionals if you acquire

malaria-possible symptoms.

- Malaria prevention is complicated, so only trust a high quality travel clinic to

prescribe the proper medications for your specific destinations and singular physiology.

-

- Chloroquine (brand names Aralen, Avloclor, and Resochin) should be

taken weekly beginning at least one week before entering a malarial area, and continuing

four weeks after leaving. Beginning the regimen two weeks before departure is often

recommended so there will be time to change medication in case of reaction. It's

traditional to take chloroquine--and to remind other travelers to do so--on Sunday.

- In falciparum malarial areas, such as Panama east of the canal, a weekly dose of

mefloquine (brand name Lariam) may be prescribed. Three tablets of

sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (brand name Fansidar) may be prescribed to be taken

immediately if flue-like symptoms suddenly develop. Some people have severe skin reactions

to Fansidar, and various neurological, psychiatric, and flue-mimicking symptoms

have been ascribed to Lariam.

- Chloroquine and the other anti-malarial drugs are not vaccines, and they do not

guarantee immunity from infection. They are prophylactic medications--taken properly, they

usually suppress and prevent malaria. Thus most travelers who take the proper

medications, use DEET insect repellent (detailed below in How to Avoid

Insect Bites), wear long sleeves and pants, and drape mosquito netting around their

beds don't get malaria.

- Yellow fever

- is a viral, hemorrhagic (bleeding) disease transmitted in urban areas from person to

person by Aëdes aegypti mosquitoes, which feed during the day. In jungle areas it is

transmitted from monkey to man by various mosquitoes. Yellow fever is found east of the

Panama canal, in parts of South America, and in much of Africa.

- Symptoms begin three to six days after infection, are relatively mild in eighty percent

of cases, and include fever, headache, and weakness, which last up to four days. The other

twenty percent are more serious, including high fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, bleeding

from the gums and nose, and severe pain in the neck, back, and legs. These may last a few

days, followed by a remission, and then followed by a more severe illness, including

increased fever, vomiting of blood, and jaundice due to liver damage--hence the name

yellow fever. Approximately five percent of all victims die within days of symptom-onset.

- Treatment consists of maintaining blood volume and fluids. No drug works against this

virus.

- Prevention is by the yellow fever vaccine, which lasts ten years. A yellow fever

vaccination certificate (yellow card) is required for entry into and from countries where

the disease is prevalent.

- Dengue fever (pron. den gay)

- is also called breakbone fever after the debilitating pain it causes. It is another

viral, hemorrhagic disease transmitted by day-feeding Aëdes aegypti mosquitoes, and thus

found in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide. While I was in the Petén region of

Guatemala an epidemic of dengue was ravaging the local population.

- Symptoms appear five to eight days after a bite from an infected mosquito, and include

high fever, severe muscle and joint pain, and rash. They subside and recur about every

three days. Recovery takes several weeks, with victims rarely dying.

- Treatment is with pain killers to relieve symptoms--there is no specific

treatment.

-

- Prevention is, as always, by avoiding mosquito bites. There is no vaccine.

- Chagas' disease

- is also called American sleeping sickness, and can be fatal. It is transmitted by the

bite of the assassin bug, which makes its home in thatched roof and adobe huts in rural

Central and South America, but especially Brazil. This bug prefers to bite on the

face

and defecate. Single-celled parasites called trypanosomes enter the body, grow to

huge numbers, then attack many organs, including the heart. Diagnosis is by a hard, purple

swelling which appears on the bite site about a week later.

- Treatment is effective only if caught early.

-

- Prevention is by not sleeping in mud huts, by using mosquito netting, or by at least

sleeping in the middle of the room away from walls. This disease is extremely rare in

travelers.

- Plague

- is transmitted to humans by the bites of rodent fleas. While a few cases of plague occur

every year in the American Southwest, it is mostly a disease of South America, Africa,

Southeast Asia, and India. Plague is the "black death" that repeatedly wiped-out

Europe during the middle ages. The risk of plague to travelers is almost zero, especially

if you make a habit of not handling rats, dead or alive.

- Rabies

- is also known as hydrophobia, and is an acute viral disease of the nervous system. Almost

invariably fatal if left untreated, it is transmitted by animal bites, scratches, or even

licks on an open cut. There are about 30,000 deaths every year from rabies, nearly all in

developing countries.

- Skunks, raccoons, and bats are the major carriers in North America. In Central and South

America dogs and vampire bats are the primary vectors. Rabies is fairly common in some

areas. Stray dogs are numerous, and vampire bats are a threat to those sleeping outside

without mosquito netting. A vampire bat lands near a sleeping mammal, creeps up, and

delivers a painless bite with razor-sharp teeth. It then laps up the blood, which doesn't

coagulate due to inhibitors on the tongue. Horses and cattle are the usual prey, not

backpackers. Any bat found on the ground is quite possibly a rabies victim. Do not touch

it.

- Jackals are the primary carriers of rabies in Africa. In Southeast Asia and India dogs

are the leading vectors to humans. Note, however, that any mammal bite may transmit

rabies.

- Ireland, Britain, Norway, Sweden, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand do not have the

disease, and require an extensive quarantine for pets entering the country.

- Symptoms of rabies begin from nine days to many months after exposure. These include

fever, hyperactivity, seizures, and often an intense thirst that cannot be quenched since

liquids produce violent and painful spasms in the throat. The victim will die within three

to twenty days from onset of symptoms.

- Prevention and treatment is through passive immunization before

symptoms

appear, and ideally within two days of exposure. Competent medical advice should be

immediately sought after a bite in a rabies endemic country. (Not a snake doctor.) Clean

the wound thoroughly with soap and clean water for at least five minutes, but don't stitch

it closed. The sooner vaccination is begun, the better the prognosis. Today's vaccines are

not so painful, and are no longer given through the stomach.

- Brucellosis

- is a rare bacterial infection in the U.S., but travelers who drink unpasteurized dairy

products in Latin America and Mediterranean countries may be at risk. Symptoms include

high fever, shaking, sweating, and severe depression. Treatment is with antibiotics and

rest.

- Schistosomiasis (bilharziasis)

- is common in tropical regions worldwide, affecting about 200 million people. It is

caused by several species of flukes (flattened worms) called shistosomes. They live in

fresh water lakes and rivers, where they live part of their life cycle in snails.

- Symptoms vary from none to serious. The first is usually an itchy rash where

the parasite has burrowed through the skin. Weeks later flu-like symptoms may begin,

including high fever, chills, muscle aches, and diarrhea. The symptoms may go away and

recur a month or two later. Long-term damage includes cirrhosis and kidney failure.

- Treatment is with a single dose of an anthelminthic (antiparasitic) drug, which kills

the flukes. Prevention is by avoiding freshwater rivers and lakes in the tropics, but

especially the Nile Valley, where schistosomiasis is rife.

- Leishmaniasis

- is a variety of diseases caused by a single-celled parasite transmitted via sandfly

bites. Some varieties affect mostly the skin, producing large ulcers at the bite area. In

the Middle East this is known as the Baghdad boil. South American forms of the disease may

cause more severe tissue damage, especially to the face. Another variety, called kala

azar, causes internal organ damage.

- Treatment is effective with sodium stibogluconate. Prevention is by avoiding sand fly

bites by wearing shoes, socks, pants, long-sleeves, and by using DEET.

- Filariasis

- is a variety of tropical diseases caused by larvae or worms, and transmitted to man by

insects. These diseases include the childhood bugaboo elephantitis, which causes

enlargement and hardening of arms, legs, and scrota, and onchocerciasis, below.

- Onchocerciasis (river blindness)

- is caused by a worm infestation in Central and South America, and Africa. The parasite

is transmitted from person to person by the black simulium fly, which is found only near

fast-moving rivers and streams. Up to twenty million people are affected, causing

blindness in many. In some African villages fifty percent of the old people have river

blindness.

- Treatment is with the drug diethylcarbamazine, which must be administered under close

medical supervision since severe reactions to the dead and dying worms may occur.

Prevention is by avoiding black fly bites.

- Giardiasis (beaver fever)

- is the bane of wilderness backpackers in the United States. It is also found worldwide,

especially in the tropics and the public water systems of the former Soviet Union. It is

an intestinal infection caused by a single-celled parasite. Wilderness backpackers in the

U.S. must treat all water, even from crystal clear brooks in Yosemite, due to the

prevalence of this organism.

- Giardia cysts (eggs) are spread from the feces of infected animals. The cysts hatch two

or three weeks after ingestion, causing abdominal symptoms such as violent diarrhea,

foul-smelling gas, and cramps. Sixty percent of those infected, however, show no symptoms.

Giardiasis clears up on its own after two or three weeks, although metronidazole speeds

recovery.

- Prevention is by drinking only pure or treated water.

Women's Concerns

- Cystitis

- is a common infection of the urinary tract and bladder among

travelers. The main symptom is a frequent urge to urinate, accompanied by burning

or stinging. The amount of urine passed is usually small, and the pain can be great.

Cystitis is sometimes associated with sex, and symptoms are similar to several sexually

transmitted diseases which can lead to infertility and cancer if not properly treated.

Therefore a doctor must always be consulted.

-

- Treatment is with an antibiotic to eliminate the infection and

prevent it from spreading to the kidneys. Drink large quantities of liquids, especially

cranberry juice, to speed recovery and as a possible preventative.

-

- Initial pain can be relieved with the urinary tract analgesic

phenazopyridine hydrochloride, available through prescription (Pyridium) or over

the counter (ask a pharmacist). This is a pain reliever, not an infection fighter, so

again, a doctor must always be consulted, perhaps especially if symptoms seem to

go away on their own.

- Vaginal infections

- Tropical climates and taking antibiotics for diarrhea and other

ailments may increase incidence, which may be reduced by wearing light, loose

clothing, and cotton underwear instead of nylon.

- Pregnant

- women should consult their doctor before traveling to developing

countries. Some vaccinations, antibiotics, and antimalarials may be harmful to the fetus.

Nearly 20,000 people are infected every day.

The hardest hit area is sub-Saharan Africa, where AIDS is called "slim" due

to its wasting effects. In some areas up to twenty percent of the population are carriers,

as well as nearly all prostitutes. In Africa AIDS is spread primarily through heterosexual

sex. The blood supply in Africa is likely to be poorly screened, if at all, so you must

avoid transfusions. Travelers in Africa should bring their own hypodermic needles for

emergencies.

AIDS is also spreading rapidly in Asia, again primarily through heterosexual contact.

Since the epidemic became widespread there only a few years ago, deaths are still rare.

Thailand is the main foci, with a significant percentage of prostitutes infected. In 1996

over three million cases of HIV (the virus that eventually causes AIDS) infection were

estimated in India--this number will mushroom.

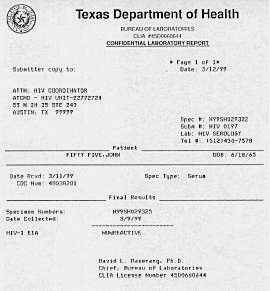

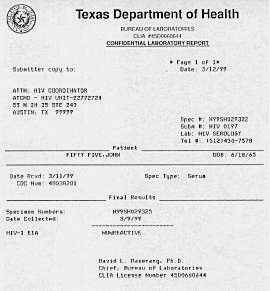

| Many countries now require HIV testing for long-term visitors of greater than six

months, or applicants for work or residency. In most cases HIV testing is not required for

visitors of a few months or less.

As you travel remember that most HIV carriers--whoever they are--don't know they're

infected, and HIV is thought most infectious the first year after infection.

|

|

| Perspectivizer--get one today. |

Insects, Worms, Single-Celled Animals, and Urine Fish

- Jiggers

- are also called burrowing fleas, and are a type of sandfly found in tropical areas of

the Americas and Africa.. They burrow between toes and under toenails, where eggs are

deposited under the skin. Symptoms are a painful and itchy pea-sized swelling. Treatment

is by removing the jigger with a sterile needle, and thoroughly cleaning with antiseptic.

Prevention is by wearing shoes or at least sandals, and by keeping nails well-trimmed.

- Chiggers

- are found worldwide on grass and weeds. These red mites attach themselves to bare legs

and ankles and feed on blood. They may cause a painful, itchy swelling about a half inch

in diameter. Prevention is by wearing socks and pants, and by applying DEET to exposed

skin, socks, and pant cuffs.

- Bedbugs

- are small, flat, usually brown bugs. They live in beds and furniture during the day, and

come out at night. Bedbugs often leave a straight line of red bites across the skin. They

rarely spread disease, but the bites should be cleaned with antiseptic to prevent

infection. Avoid bedbugs by checking bedding carefully--look for tiny red splotches on

sheets and blankets. If you see their sign, take another room or string-up your hammock.

|

Left: These are large black ants. The

column is about a foot wide. |

|

|

Right: Here large red ants rampaged a 20 by 20 foot area, attacking and

devouring insects across the jungle floor. Very interesting to watch. They ignored me. |

- Sandflies

- are tiny, nearly-invisible long-legged flies common to tropical areas. Sandflies can

transmit several diseases to humans, including leishmaniasis, bartonellosis (in the

Andes), and sandfly fever.

- Since sandflies are most active at dawn and dusk, walking at those times stirs them up

and results in numerous, amazingly irritating bites. You won't be bothered as much if you

sensibly remain in, or retreat to, your hammock during dawn and dusk. Also cover exposed

skin, especially legs, ankles, and arms, and use DEET. Socks help a lot.

- Lice

- are tiny, flat, wingless bugs. Body lice are killed by washing clothes in very hot

water, or by using a hot dryer. Head and pubic lice can be killed with lotions and

shampoos containing benzene hexachloride.

- Scabies

- are tiny mites that burrow into the skin, lay eggs, and cause intense itching,

especially at night. Treatment is with an insecticide lotion.

- Hookworms

- are half-inch long worms that live in the small intestines of 700 million people

around the world, especially in the tropics. They have hook-like teeth. Their life cycle

begins with larvae burrowing into the feet, or by ingestion. A large infestation of

several hundred hookworms may eat several ounces of blood per day, causing anemia.

- Symptoms, called ground itch, may include a red and very itchy rash on

the feet that lasts for several days. A cough and pneumonia are also possible when a heavy

infestation passes through the lungs.

- Prevention is by wearing shoes or sandals. Treatment is with an anti-worm drug.

- Guinea worm

- is the "fiery serpent" scourge of the Biblical Israelites. It

is an up-to three-foot long female worm that now plagues eighteen African and Asian

countries, although recently eliminated from Pakistan. Infection is by drinking water

containing the cyclops crustacean water flea.

Symptoms begin a year later when the worm

is fully grown and ready to reproduce. It comes to the surface of the skin where a blister

forms. Hives, diarrhea, and vomiting often occur at this time. When the blister bursts the

end of the worm is exposed, and debilitating pain begins.

The traditional treatment is to wrap the exposed worm around a stick, and then gently

wind it out over several days. This is dangerous (although impressive) as the worm can

break and an infection develop.

As guinea worm must live part of its life cycle in man, it is only the second disease

(after smallpox) targeted by the World Health Organization for eradication, aided by great

diplomatic imprimatur from the Carter Center.

- Beefworm (botfly larvae)

- is the only creature known to penetrate my defenses in Central America. It is common in

the jungles of Belize.

- The botfly is an ordinary-looking fly with unusual child-rearing habits. It captures a

mosquito in flight and lays eggs on it. The mosquito is released, and when it subsequently

bites a warm-blooded prey some of the eggs fall off and are hatched by body heat. These

creatures then burrow into the skin (my sandal-clad foot, your pretty face?) where they

feed and grow just under the skin. After several months they reach maturity, painlessly

squeeze out, and fall to the ground to continue their life cycle.

- Diagnosis is by a mosquito bite that doesn't go away. After several weeks it

resembles a boil, except for a tiny hole in the center. If you look closely with a

magnifying glass you will see something pushing to the surface every so often to breathe

and expel waste. (Yes, the botfly larvae breathes through its butt.) As it feeds it

occasionally delivers a sharp pain like a hot needle stabbing into flesh,

which lasts only a few but very long seconds.

- Treatment is simple, if you know how. You cannot just squeeze it out as the beefworm is

ringed with barbaric barbs which tightly hold flesh. And since the beefworm produces its

own antibiotic to prevent infection while alive and healthy, you don't want to rip it

apart as an infection would likely develop. The traditional Mayan method is to pour

tobacco juice into the hole, which kills the beefworm in about an hour. You then easily

squeeze it out.

- Another method which worked for me is to suffocate the beast overnight by covering the

hole with multiple layers of Elmer's glue and plastic wrap. It becomes poppable if you

manage to cut off 100% of its air. On the second try mine flew several meters through the

lower atmosphere before smashing into an obstruction.

- Tumbu fly

- This African fly lays eggs on clothing left out to dry, which later hatch with skin

contact. Results and treatment are similar to the botfly. Prevention is by ironing clothes

to kill the eggs, or by hiring fly swatters, although this is said to be unreliable.

-

- Urine fish

- Reported in some Central American rivers to also hang on with barbaric barbs. I haven't

yet determined whether urine fish are fact or of the same class as the Amazonian ear

weevil, which renders victims insane from otherworldly pain as it bores from one side of

the head to the other. (See a medical professional before developing world travel!)

Hydraulic Currents and General Lessons

How to Avoid Insect Bites

The best way to avoid malaria and over one-hundred other mosquito and insect-borne

diseases is to avoid being bitten in the first place. Since only some insects are disease

carriers, you vastly reduce your chance of infection by limiting the number of bites.

Furthermore, it may take more than one bite from a disease-carrying insect to transmit

disease.

The first line of defense is long sleeves and pants. In jungle areas I'm much more

comfortable wearing loose-fitting cotton pants and a long-sleeved cotton shirt. They are

plenty cool and dramatically reduce every kind of insect bite. Note that mosquitoes can

slide their proboscises through a knit or too-thin shirt. Light colors such as khaki are

less attractive to mosquitoes.

The second mosquito defense is DEET (diethyl-meta-toluamide). This is

a powerful (it melts some plastic) insect repellent recommended and used world-wide. While

the FDA is currently investigating possible side-effects in children, it has stated the

benefits of DEET far outweigh these side effects, which are likely to be minor. Indeed,

not contracting malaria and other insect-borne diseases is priceless.

DEET repellent should be applied following the manufacturer's instructions to all

exposed skin. Do not apply it under clothing. Many travelers also apply DEET to sleeves,

collars, socks, and cuffs to further discourage bugs.

Some DEET products consist of a

100% formulation for maximum effectiveness of up to eight or ten hours. 3M makes Ultrathon,

a 33% DEET product with a special carrier which slowly releases the DEET for a claimed

effectiveness of up to twelve hours. Ultrathon is also absorbed less through the skin,

thus making it safer than 100% DEET. The CDC recommends formulations from about 25 to 35%.

Some DEET products consist of a

100% formulation for maximum effectiveness of up to eight or ten hours. 3M makes Ultrathon,

a 33% DEET product with a special carrier which slowly releases the DEET for a claimed

effectiveness of up to twelve hours. Ultrathon is also absorbed less through the skin,

thus making it safer than 100% DEET. The CDC recommends formulations from about 25 to 35%.

I've used Ultrathon in a tube with good results. Many health care professionals

recommend it. It also comes in a spray can with a 23% formulation which lasts up to eight

hours, and is better for sensitive skin. The tube is lighter and lasts longer.

I reapply a little Ultrathon cream every few hours while hiking since all DEET products

lose effectiveness as you sweat.

Other Mosquito Defenses

Permethrin is an effective repellent which is only approved for

application to clothing and mosquito netting, not skin. It is considered safe when used in

this manner. Permanone, Coulstan's Duranon, and Sawyer are brand

names of permethrin aerosol spray marketed as tick repellents. One good spray treatment

lasts several weeks. Coulston's Perma-Kill 4-Week Tick Killer is a liquid which

lasts four weeks on clothing, longer on mosquito netting.

Permethrin is an effective repellent which is only approved for

application to clothing and mosquito netting, not skin. It is considered safe when used in

this manner. Permanone, Coulstan's Duranon, and Sawyer are brand

names of permethrin aerosol spray marketed as tick repellents. One good spray treatment

lasts several weeks. Coulston's Perma-Kill 4-Week Tick Killer is a liquid which

lasts four weeks on clothing, longer on mosquito netting.

Mosquito netting is essential for sleeping in the tropics. It drapes around your bed or

hammock from a hook or line strung above it. While many hotels in the tropics lack

screens, they often have fans which produce enough breeze to prevent mosquitoes from

landing. Unfortunately, you can count on electric power regularly going out.

Mosquito netting with too-fine mesh can be stifling. On the other hand if the mesh is

too coarse black flies and no-see-ums can penetrate. Spraying or soaking mosquito netting

in permethrin dramatically increases effectiveness. Store the net in a plastic bag to keep

the permethrin effective longer. Be certain there are no gaps or holes in the netting

around you, and that no part of your body rests against it, as mosquitoes are seriously

bloodthirsty. Make sure there are no mosquitoes already inside the netting.

Mosquito head nets may also be useful. I used one while summer camping in Norway where

the mosquitoes were frighteningly monstrous and multitudinous. (Two could whip a dog,

four could hold down a man and butcher him--Mark Twain.) Head nets alone are not

enough in malarial areas, though.

Mosquito coils are spiral-shaped candles that repel mosquitoes and other bugs with the

natural chemical pyrethrum. They burn for several hours, and are useful when cooking

dinner while camping, or in hotel rooms without screening. Cintronella is another natural

repellent adequate for backyard use in the States, but not effective in serious biting

insect areas where efficacy is vital.

Insects are also attracted to scents, so don't wear perfume or cologne, or use scented

soaps, shampoos, or deodorants. Unscented deodorants are available. Several women have advised that Avon's Skin So Soft lotion fends off

minor backyard flying insects in the U.S.

Mosquitoes do not attack as long as you walk at a fair pace, or if there is a breeze.

They wait for the wind to calm, the electricity to shut off, or for you to fall dead from

exhaustion.

Cuts, blisters, and other wounds can become infected very fast in the tropics due to

the rich microbial environment. Great care must be taken to thoroughly clean wounds, and

to treat with an antiseptic such as tincture of iodine, which is good because it also

kills viruses. Keep wounds covered with a clean bandage and recheck. Double-strength

triple antibiotic ointments such as Neosporin are also helpful.

Rashes

To combat itching from stings and plants in the tropics, be sure to have antihistamine

pills and a tube of 1% hydrocortisone anti-itch cream. After two mysterious, expanding red

rashes appeared on the back of my leg, you can bet I'll never again travel in itch country

without serious anti-itch medication.

I may have crushed a poisonous millipede between my calf and thigh. While I didn't feel

anything, I noticed two small, elongated black spots which looked like burns. I

should have immediately irrigated with water and wiped with alcohol to remove as much

poison as possible. Instead I ignored the situation for two days. Gradually the poison

expanded about three inches beyond the initial sites, creating two purple and red, excruciatingly

3 itchy rashes. By scratching I

transferred poison to other parts of my body.4

Calamine lotion was next to useless. Benadryl antihistamine pills worked well. I later

discovered 1% hydrocortisone cream also works well. There is a new Benadryl cream which is

probably effective.

Plants and stings that cause nasty itching are a surprisingly effective and common

defense. The best counter-defense is always a layer of clothing and shoe leather.

If afflicted take immediate action by washing the affected area with water, beer, or

spit. Run water over it for ten or more minutes if possible. (For a cobra sting

run it

all night.) Then disinfect with soap or alcohol. Again, in the tropics you

risk infection by scratching severe itches.

Foot Care and Blisters

This is probably the #1 backpacker health concern. Have a thick pair of socks such as

Thorlo in your pack in case blisters develop. Also, at the very first sign of a "hot

spot," take action. Don't trudge on doing more damage than necessary. Allow the

healing process to begin sooner on something not so bad, as opposed to later on worse.

I keep a piece of Compeed, a great blister product, in my wallet, more in my

pack. When you do get a blister it may be miles to the nearest pharmacy, which is too far,

too late. Duct tape, Moleskin, and a liquid product called NuSkin also work.

Blisters become easily infected in the tropics, so be extra careful to avoid them, and

keep them clean and disinfected when they develop. If you decide to pop a blister, use a

sterilized needle and apply antiseptic. Cover and check regularly.

I also have a 1/3 ounce (10 milliliter) plastic bottle of Lotrimin AF

(clotrimazole) antifungal solution in my medical kit to treat fungal infections. (I just

noticed the use-by date has expired.) An effective antifungal is necessary to treat

athlete's foot, ringworm, and other unusual skin infections which may crop-up during

extended tropical travels.

Effects of the Sun

In rural Mexico I came across an Austrian traveler who had been wandering three weeks

without hat or sunblock. He was as red as a beet, and obviously dazed from

excess solar radiation. Weakly pointing to my straw cowboy hat, he mumbled, "That's what

I need..."

The sun is very intense in the tropics and at higher elevation. For every 5000 feet

(1500 meters) in altitude gain, UVB radiation increases by twenty percent. Travelers

should wear a hat with at least a three-inch brim all around, and use sunblock with a sun

protection factor of at least fifteen.

Sunglasses with ninety-nine percent UVA/UVB protection will be much desired by the

hitchhiking traveler, and protective goggles are a must for preventing snowblindness at

altitude.

Heat and Humidity

In one to three weeks the body gradually acclimates to heat through a physiological

process. Unacclimated travelers run a risk of heat exhaustion or heat stroke if they try

to do too much, too soon.

|

If you are AC-addicted or from a cool climate, use caution and

allow time--soon the

hot environment will seem cooler. Knowing your body is adjusting should be a comfort. |

| Photo: Here I'm jungle trekking and

drinking six quarts per day. |

Travelers may be able to partially acclimate themselves to a hot environment like Egypt

by taking daily saunas for a week or two before departure, gradually building exposure

levels.

High humidity is the worst aspect of the tropics for many travelers. Wear loose cotton

clothing and drink lots of clean water. A wet bandanna around your neck or forehead

provides good cooling.

Prickly heat is a red rash which occurs under clothing. I've had it a few times on my

legs before becoming acclimated. It has a moderate prickly feeling, and goes away after a

day or two. Prickly heat is assuaged by cool showers, cold water sponging, calamine

lotion, and loose-fitting, breathable clothing. In my case clothing should also be

well-rinsed of detergent, which is harsh in developing countries.

- Heat exhaustion

- is caused by overexposure to heat by a non-acclimated person, or insufficient water or

salt intake by any person.

- Symptoms include fatigue, dizziness, nausea, headache, and possibly muscle cramps.

Treatment consists of rest, shade, and drinking water at a slow but steady rate, including

water with a weak salt solution of approximately 1/4 teaspoon per eight-ounce (1/4 liter)

glass. Cool the body with water, wet towels, and a fan, if possible. If the victim becomes

unconscious, feet should be raised twelve inches above the head.

- After twelve miles of jungle hiking in one day--half with a pack--I suddenly realized I

had heat exhaustion as I had stopped sweating and was beginning to feel nauseated. I had

drunk several liters of water that day, but that was far from enough. Luckily I was only

half a mile from camp (I was on a night hike), so I immediately returned and slowly drank

two more liters of water. I had moderate nausea and chills, and felt terrible. In the

morning I was much better and drank several more liters.

- Heat stroke

- follows untreated heat exhaustion. It often results in rapid death due to a breakdown of

the body's heat regulating mechanisms. Body temperatures can reach soaring levels.

- Symptoms usually include a cessation of sweating; shallow breathing; hot, dry, and

flushed skin; unconsciousness; and if conscious, disorientation or stupor.

- Treatment must be immediate. The victim should be placed in shade and his body cooled as

quickly as possible. Remove all clothing and wrap him in wet towels, or sponge the body

continuously with cool water. Direct a fan at the victim. If unconscious, raise feet

twelve inches. If conscious, give the victim water, preferably with 1/4 teaspoon salt per

eight-ounce (1/4 liter) glass. Medical help must be summoned.

- Hypothermia

- is a life-threatening condition defined as body temperature below 95º F (35º C).

Temperatures do not have to be extreme to cause hypothermia, since water and wind can

combine to rapidly chill a person. Most deaths from hypothermia occur in well-above

freezing temperatures.

- Symptoms include a pale, drowsy, confused, and cold victim. She may become unconscious.

Treatment consists of seeking immediate medical help and warming the victim. Warm drinks

are effective, as well as hats, blankets, emergency aluminum blankets which reflect body

heat, and, of course, warm shelter. Remove wet clothing.

- Prevention is by wearing warm clothing in insulating layers, a windproof/waterproof

shell, and a hat. An aluminum reflective space blanket should be in every traveler's pack.

Avoid cotton clothing in cold, wet conditions.

- Frostbite

- must be treated immediately by warming affected areas. Massage is not helpful, but

placing feet and hands under armpits is. If warm water is available, place the affected

areas in it. The water should not be hotter than 110º F (43º C). Remove constricting

clothing, rings, and watches. Don't warm affected areas with direct heat, such as from a

lighter. Don't allow someone to walk on a frostbitten foot, unless it's necessary for

survival.

Altitude sickness is also called acute mountain sickness (AMS). It occurs when

ascending to altitude before the body has time to adjust to the lower air pressure and

lower oxygen content of the air. It usually occurs at altitudes above 8000 feet (2500

meters). About twenty-five percent of travelers to high altitudes will be affected, but

younger people are more susceptible.

Symptoms are usually mild and flu-like, such as headache, shortness of breath,

dizziness, nausea, and fatigue. Insomnia often results due to shortness of breath. Usually

these symptoms last only a short time as the body adjusts. Many travelers have trouble

sleeping their first night or two in high altitude cities such as Quito, Ecuador (9350

feet or 2850 meters).

Severe cases result in fluid buildup in the lungs. This leads to intense

breathlessness, coughing and wheezing. Fluid may also build-up in the brain, leading to

severe headache, seizures, vomiting, hallucinations, and even coma.

Treatment for mild cases is usually just rest. Plan for an easy day or two upon landing

in Quito. Aspirin may help. Avoid alcohol and drink plenty of fluids. Locals drink coca

tea to alleviate symptoms. It acts as a mild stimulant and pain killer.

Treatment for severe cases requires immediate action--if you wait until morning the

victim may die or suffer brain damage. She should be brought down at least two or three

thousand feet and have oxygen administered. She should also be brought to a hospital as

soon as possible where diuretic drugs may be given.

Prevention is best by slowly gaining altitude. If you walk to gain altitude you can go

back down a few thousand feet if you begin feeling symptoms. One rule of thumb is to

always sleep below the highest altitude achieved that day.

Motion Sickness

If you are susceptible to motion sickness, Dramamine pills work better if

taken before symptoms develop. Scopolamine ear patches may also help. While at

sea or riding a bus get as much fresh air as possible, and focus vision towards the

horizon--not the chicken cage next to you. Think pleasant thoughts. Avoid greasy or spicy

foods. During an attempt to earn travel money on the Bering Sea my bargemates and I ate

crackers to alleviate queasiness.

Jet lag isn't much of a problem for most backpackers. We don't have to be up for an

important meeting at a certain time, and for the first few days can simply rest when we

need to. Our internal clocks adjust to the new sunlight and social schedule within a few

days. Traveling east, say from the Americas to Europe, takes a slightly longer adjustment

period since you must begin sleep earlier to synchronize with the environment. Traveling

west mainly requires staying up extra late. Jet lag is more of a problem for anachronistic

Chinese leaders experiencing democracy and rule of law for the first time/people on

speeding bus tours.

Note that airplane air is extremely dry (one or two percent humidity), so on transocean

flights drink plenty of fluids to avoid partial dehydration on your very first day.

Backpackers' Medical Kits

Right now in my pack I have a quart-sized plastic zip bag I call a medical kit. It

consists of a few band-aids, larger bandages, and butterfly closures; a few yards of cloth

tape wrapped around a pencil; a one-ounce dropper bottle of iodine antiseptic; a 1/2 ounce

(15 milliliter) tube of triple antibiotic ointment; an unopened bottle of Potable Aqua water

disinfectant tablets;  Compeed blister pads; a 1/3 ounce (10 milliliter) bottle of

Lotrimin AF antifungal solution; a 1/2 ounce tube of Cortaid 1% hydrocortisone anti-itch

cream; aspirin; a thermometer in a taped-shut plastic case; tweezers; twelve Immodium

tablets; ten chewable Pepto Bismol tablets; ten antihistamine pills; twelve Ciprofloxin

antibiotic capsules as prescribed by my travel clinic; a packet of rehydration salts; and

144 condoms.

Compeed blister pads; a 1/3 ounce (10 milliliter) bottle of

Lotrimin AF antifungal solution; a 1/2 ounce tube of Cortaid 1% hydrocortisone anti-itch

cream; aspirin; a thermometer in a taped-shut plastic case; tweezers; twelve Immodium

tablets; ten chewable Pepto Bismol tablets; ten antihistamine pills; twelve Ciprofloxin

antibiotic capsules as prescribed by my travel clinic; a packet of rehydration salts; and

144 condoms.

Additional medical items elsewhere in the pack are small folding scissors;

one-a-day-type vitamins; duct tape; a small piece of Compeed or Moleskin in my wallet; and

a four-ounce bottle of rubbing alcohol which I use for disinfecting hands when soap and

water isn't convenient.

Before my next trip to the developing world my travel clinic will prescribe a

combination of anti-malarial pills, another antibiotic, and possibly a sterile syringe and

needle.

Outdoor shops and catalogers sell pre-assembled medical kits that range in price from

$8 to over $100. They don't contain doctor-prescribed antibiotics or medicines. I've

always assembled my own. See Chapter 23-b Useful Information

for two companies that specialize in medical kits.

Upon Returning Home

If you come down with an illness soon after returning from the developing world, inform

your doctor of that fact. Many tropical diseases are very difficult to diagnose, and mimic

the flu. You may need to see a tropical disease specialist. You may also want stool and

blood tests to see if anything unusual is lurking about. Otherwise wait two years

to see if your stool becomes bloody and lower intestine blocked by a gigantic mass of

ascaris lumbricoides, or other.

Travelers' Tips

Make a notecard of your medical history and keep it in your wallet. Indicate

whether you have any known food and drug allergies, and any known health conditions. Also

your blood type, and any other instructions. Several companies, such as Medic-Alert, make

bracelets and chains which also contain this information. Aida, Brooklyn

*

Beware of salads, especially lettuce, in developing countries with suspect water

supplies. The rule is if you can't wash it, peel it, or boil it, don't eat it. Lisa,

Christchurch, New Zealand

*

When we arrived in Sri Lanka and engaged a driver with car we

insisted on having a car with seat belts....We may owe our lives to this because after ten

days our driver went off the road and down a six metre drop into a culvert. We were

wearing belts and so--for the first time--was our driver. We all walked away...thankfully

with no serious injuries. Andrew, UK

*

My schedule will be drastically compressed if the test comes back positive in five

and a half months. Turbo, USA

How to See the World is copyright © John Gregory 1995-2009. All rights reserved. Except

for personal use like showing to a friend, it may not be reproduced, retransmitted,

rewritten, altered, or framed. All

product names and trademarks are property of their respective

owners. Comment.

Sales.

Disclaimer. Thank you.

............

.

|

|

. |

. |

....... .

. |

.. |

.. |

. |

.`

|

| ....... |

:)

. |

. |

. |

..... |

.. |

.. |

. |

. |

| . |

. |

|

. |

. |

. |

|

. |

. |

| . |

|

. |

. |

...............

. |

. |

. |

|

. |

| |

. |

. |

. |

......................................... . |

. |

. |

. |

|

| ......

.............. |

. |

. |

. |

ARTOFTRAVEL.COM

.

|

. |

|

(: |

..

.

.

......... . |

| . |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

Notes

1. My rough calculation: 50,000 automobile deaths per year x 70 year

lifespan = 3.5 million total deaths. 350 million projected population ÷ 3.5 million =

100, or a 1 in 100 chance. back

2. After a years-long night and first light filtered through the front of

the bus I cried out to myself, Thank God! We're there! But nay, it was five

hundred miles and many mountains, many mountains to go. back

3. Chosen over torturously, because in uncivilized countries that's a

lifetime punishment for thinking and speaking. back

4. O to learn. back

Some DEET products consist of a

100% formulation for maximum effectiveness of up to eight or ten hours. 3M makes Ultrathon,

a 33% DEET product with a special carrier which slowly releases the DEET for a claimed

effectiveness of up to twelve hours. Ultrathon is also absorbed less through the skin,

thus making it safer than 100% DEET. The CDC recommends formulations from about 25 to 35%.

Some DEET products consist of a

100% formulation for maximum effectiveness of up to eight or ten hours. 3M makes Ultrathon,

a 33% DEET product with a special carrier which slowly releases the DEET for a claimed

effectiveness of up to twelve hours. Ultrathon is also absorbed less through the skin,

thus making it safer than 100% DEET. The CDC recommends formulations from about 25 to 35%. Permethrin is an effective repellent which is only approved for

application to clothing and mosquito netting, not skin. It is considered safe when used in

this manner. Permanone, Coulstan's Duranon, and Sawyer are brand

names of permethrin aerosol spray marketed as tick repellents. One good spray treatment

lasts several weeks. Coulston's Perma-Kill 4-Week Tick Killer is a liquid which

lasts four weeks on clothing, longer on mosquito netting.

Permethrin is an effective repellent which is only approved for

application to clothing and mosquito netting, not skin. It is considered safe when used in

this manner. Permanone, Coulstan's Duranon, and Sawyer are brand

names of permethrin aerosol spray marketed as tick repellents. One good spray treatment

lasts several weeks. Coulston's Perma-Kill 4-Week Tick Killer is a liquid which

lasts four weeks on clothing, longer on mosquito netting.

Compeed blister pads; a 1/3 ounce (10 milliliter) bottle of

Lotrimin AF antifungal solution; a 1/2 ounce tube of Cortaid 1% hydrocortisone anti-itch

cream; aspirin; a thermometer in a taped-shut plastic case; tweezers; twelve Immodium

tablets; ten chewable Pepto Bismol tablets; ten antihistamine pills; twelve Ciprofloxin

antibiotic capsules as prescribed by my travel clinic; a packet of rehydration salts; and

144 condoms.

Compeed blister pads; a 1/3 ounce (10 milliliter) bottle of

Lotrimin AF antifungal solution; a 1/2 ounce tube of Cortaid 1% hydrocortisone anti-itch

cream; aspirin; a thermometer in a taped-shut plastic case; tweezers; twelve Immodium

tablets; ten chewable Pepto Bismol tablets; ten antihistamine pills; twelve Ciprofloxin

antibiotic capsules as prescribed by my travel clinic; a packet of rehydration salts; and

144 condoms.